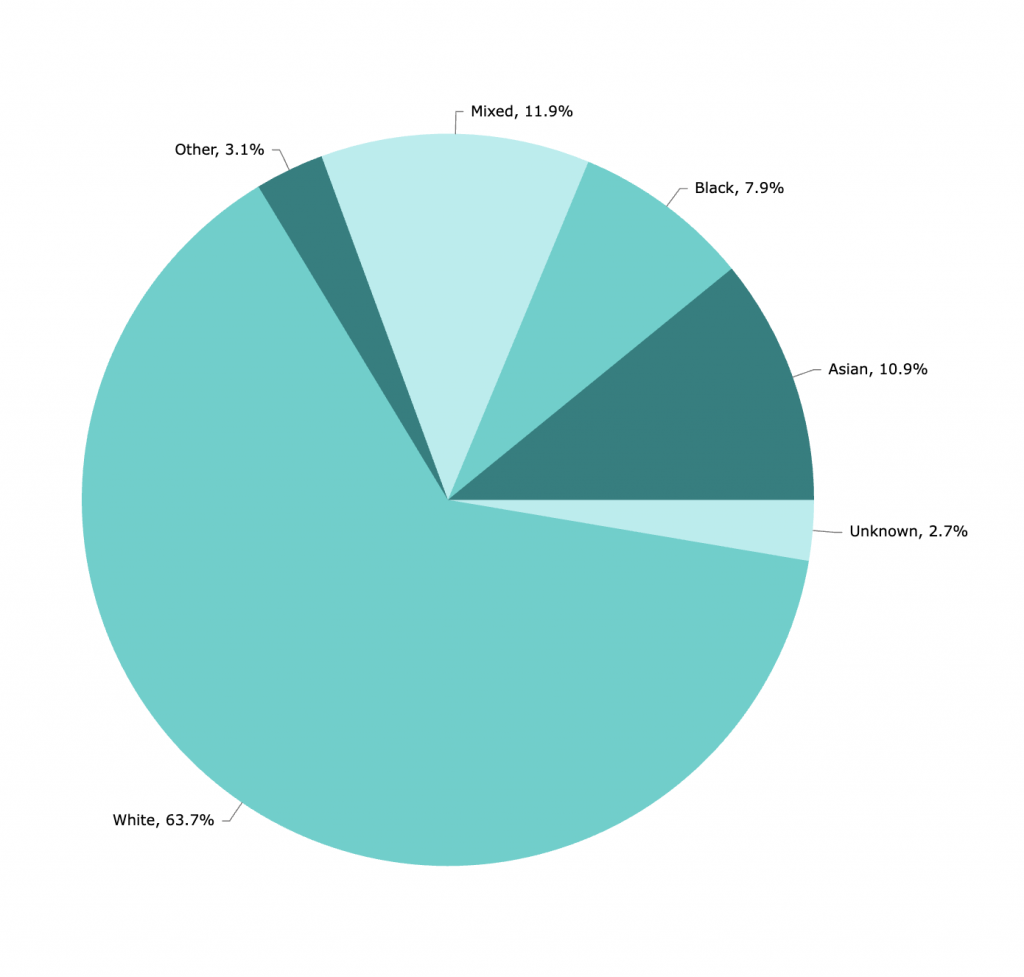

3. Race and Language

In this blog, I will reflect on the intersection of race and language, specifically on how this influences perceptions of academic authority experienced by students (and also academics). This is important in my context as an academic supporting students’ learning, including PhD students, where issues of voice, credibility, and recognition tend to affect academic progress and confidence.

It is no surprise that the way students and academics sound and present themselves influences how they are perceived. One element is accents, which carry strong social meanings and assumptions. Studies demonstrate that British accents associated with white, middle-class regions (like Received Pronunciation) are seen as more trustworthy or authoritative. Meanwhile, accents linked to racialised or working-class communities are viewed as less competent (Coupland and Bishop, 2007).

But it is not just how we ‘hear’ and ‘read’ language in isolation that has an impact. As Nelson Flores and Jonathan Rosa (2015) explain, people do not just judge what is being said, but who is saying it. This means that even when racialised students speak in ways that match the expected “appropriateness”* their speech is still often seen as “not quite right.” They are heard as less intelligent or less capable, simply because of who they are.

In academia, language is not just about communication, it is tied to power. Speaking in the ‘right’ way can make someone seem more knowledgeable, while anything that sounds ‘different’ can lead to being judged negatively. Rhianna Garrett (2025) gives the example of racialised academics who often find that their expertise is undervalued compared with their white counterparts. That is not because of their actual knowledge, but because they do not sound or look like what the institution expects an ‘academic’ to sound or look like. Specifically, in the arts and humanities, where frequently there are no objective ways of measuring quality, language use tends to be interpreted through subjective and culturally embedded norms, which can marginalise voices that are different from dominant academic styles.

This judgment towards students and their academics who teach them has real effects. If they are always being corrected, stigmatised, or subtly made to feel ‘less than’, their confidence starts to drop. They may not feel very confident speaking in public, feel like they don’t belong in academic spaces, or struggle to imagine themselves in certain careers. Garrett’s (2025) research shows that PhD students from racialised backgrounds experience this. Many feel like outsiders in academia and find it hard to see themselves as academics. Flores and Rosa (2015) explain that this is not because of language gaps, but because the system keeps defining success through a white, middle-class lens. So even when racialised students and academics do everything ‘right’ – adopting the right grammar, accent, and tone – they’re often still seen as not enough.

In my teaching and academic practice, I see my role as creating a learning environment where all students feel empowered to express their voices. One way I have begun addressing this issue is through my Intervention, which aims to support inclusivity by building students’ confidence in sharing their perspectives.

*“Appropriateness” is a term used by Flores and Rosa that refers to the idea that only certain ways of speaking—usually those linked to dominant white culture—are seen as correct or acceptable.

References:

Bradbury, A. (2020) ‘A critical race theory framework for education policy analysis: the case of bilingual learners and assessment policy in England’, Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(2), pp. 241–260. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2019.1599338. [Accessed 30 May 2025].

Coupland, N. and Bishop, H. (2007) ‘Ideologised values for British accents1’, Journal of Sociolinguistics, 11(1), pp. 74–93. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00311.x. [Accessed 27 June. 2025].

Flores, N. and Rosa, J. (2015) ‘Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education’, Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), pp. 149–171. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149. [Accessed 27 June. 2025].

Garrett, R. (2025) ‘Racism shapes careers: career trajectories and imagined futures of racialised minority PhDs in UK higher education’, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 23(3), pp. 683–697. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2024.2307886. [Accessed 27 June. 2025].

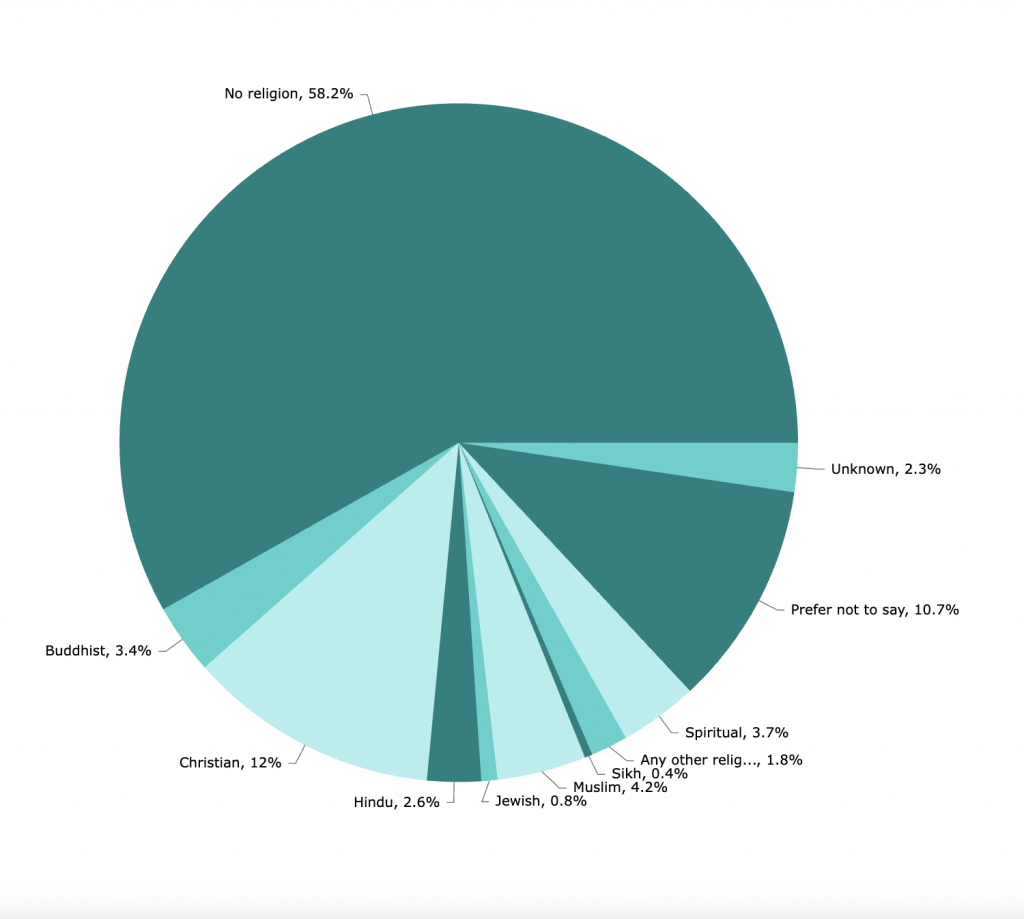

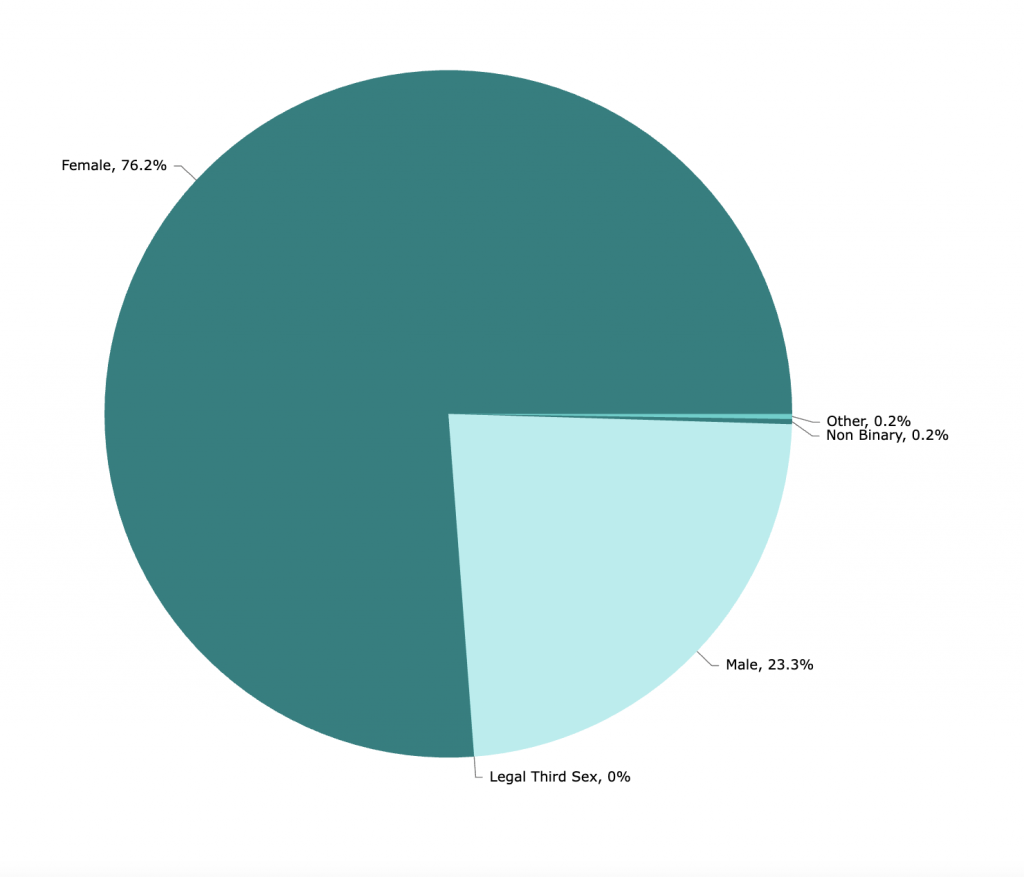

2. Faith, Religion, and Belief

I want to use this opportunity to reflect on an episode that happened a few months ago during my work at Peckham Levels, where I was managing studio spaces. I came across a group of around seven students, all of whom were Black and male, sitting around a table discussing morality, specifically, drawing from their own life experiences, families, and their religious beliefs. Considering that they all held identities often underrepresented in higher education, and especially at UAL – Black, male, and religious – the moment felt rare. I was surprised, not just by how many of them shared this identity, but also by how freely they spoke when in the company of people they seemed to identify with.

It made me question: Would they have shared their views so openly in a mixed group? Would they have discussed faith so easily in a ‘classroom’ setting? And, at a personal level: How would I be able to support these students in their work if I did not relate to their religious worldview? Not because I wouldn’t know how to support students with different views from mine, but would they feel able to express that with me? As my PGCert colleague Claire notes in her blog, it is possible that students might assume I would not respond favourably to their religious beliefs, as academic spaces often signal that faith is not intellectually valid.

Drawing on Jaclyn Rekis’ work (2023), students can experience a kind of unfairness when their way of understanding the world is not recognised in academic spaces. For religious students, this might mean their beliefs are seen as out of place or hard to talk about. And this does not always mean direct discrimination, but that there is no shared language or understanding. Keon M. McGuire (2019) shows how Black male students often experience a disconnect between their religious identities and the secular expectations of higher education. This echoes what Darren Sherkat (2007) describes as “the ugly” dimension of religion in academia, in ‘The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’, where the “ugly” refers to tensions between secular academic culture and religious identity.

In Black Bodies and the Black Church, Kelly Brown Douglas (2012) explores how the church functions as more than just a religious space in many Black communities — particularly in the North American context — but also as a source of social support. For Black men, who often face structural exclusions in both education and wider society, faith can provide resilience, pride, and a strong moral foundation.

At UAL, Black male students who are religious – and part of multiple minority groups – may feel pressure to compartmentalise their identities. As Rekis (2023) argues, this can result in a fragmented sense of self or a feeling of exclusion in institutions that fail to acknowledge religion as part of their identities.

This moment stayed with me because it made visible to me the presence of religious students who may often feel unseen. It also reminded me how important it is to create spaces beyond the typical academic studio where students can speak openly, and where shared identity might help build that confidence.

References:

Appiah, K. A. (2014) Is religion good or bad? Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2et2KO8gcY (Accessed: 28 May 2025).

Douglas, K.B. (2012) Black bodies and the Black church: a blues slant. New York: Palgrave Macmillan (Black religion/womanist thought/social justice).

McGuire, K.M. (2019) ‘Religion and Its Intersections: Spirituality, Secularism and Religion Among Black Diasporic Communities in Higher Education’, Journal of College and Character, 20(2), pp. 87–96. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587x.2019.1591282.

Sherkat, D.E. (2007) ‘Religion and Higher Education: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 612(1), pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207301321

Rekis J (2023). Religious Identity and Epistemic Injustice: An Intersectional Account. Hypatia 38, 779–800.

1. Disability: Barriers to Access in Offsite Professional Practice Spaces

Disability and socio-economic status remain persistent barriers to equal participation and success in higher education (House of Commons, 2023, p.6). While these issues affect students across all disciplines, they present particular challenges in arts Higher Education (HE), where access to physical space, materials, and peer networks plays a central role in learning and development.

In my role managing the off-site studio spaces for CCW students at Peckham Levels, I oversee the day-to-day operations and provide support for learning activities, exhibitions, and other events. The building, a repurposed car park, is largely step-free and relatively accessible to wheelchair users. However, accessibility extends beyond the building. Peckham Rye station is the closest rail connection – only a three-minute walk – if you can manage stairs. Neither Peckham Rye nor nearby stations are step-free, meaning students with mobility impairments must rely on bus routes, live locally, or fund alternative transport. In a Financial Times article about the difficulties disabled workers face commuting in London, one of the interviewers pointed out that the longer the commute, the more obstacles there are to endure, which results in greater fatigue. The alternative to transport is to find accommodation closer to work, but that will likely increase living costs. According to the 2024 Access Insights Report, 46% of disabled students who need accessible student housing have had to pay more (2024, p.38), adding to this financial strain.

The shift to online teaching during the pandemic provided some flexibility long requested by disabled students who are not able to go to college for every in-person teaching (see Suanne Gibson, 2022, p.4). But physical spaces seem to remain vital for students. Specifically, the studios at Peckham Levels offer students an environment that cannot be replicated online and even on campus: access to certain equipment, large working areas, space for exhibitions and events, and the chance to work alongside peers, the community and other professionals. Students who struggle to access these spaces due to mobility issues are clearly at a disadvantage.

But it is not only the ability to access these spaces that matters. The financial burden associated with organising events such as exhibitions puts pressure on students, who are expected to cover the cost of materials, exhibition, production, and transportation of their work. These challenges are further compounded for students with mobility issues, for whom transporting and installing work may also involve hiring assistance or specialist transport. Tasks such as moving works, navigating inaccessible infrastructure, and spending extended hours on site can be both physically and financially unfeasible. Students unable to afford regular access to these spaces and participate in opportunities like those offered by our studios at Peckham Levels miss out on the informal peer networks and curatorial initiatives that arise from being physically present.

References:

Disabled Students UK (2024) 2024 Access Insights Report. Available at: https://disabledstudents.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024-Access-Insights-Report.pdf [Accessed 30 Apr. 2025].

Financial Times. (2025). Navigating public transport and infrastructure to work. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ebdf55f4-61b8-45ed-8534-866541f29360 [Accessed 30 Apr. 2025].

Gibson, S., Shute, J., Williams-Brown, Z., & Westander, M. (2024). Higher Education and Ableism: Experiences of Disabled Students in England During the Covid-19 Pandemic – Stepping into Inclusion. Educational Futures, 15(1). Available at: https://educationstudies.org.uk/journal/ef/volume-15-1-2024/higher-education-and-ableism-experiences-of-disabled-students-in-england-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-stepping-into-inclusion/ [Accessed 30 Apr. 2025].

House of Commons Library (2023) Equality of access and outcomes in higher education in England. Briefing Paper Number CBP-9195. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9195/CBP-9195.pdf [Accessed 30 Apr. 2025].

Transport for London (2024) Step-free Tube Guide. [PDF] Available at: https://content.tfl.gov.uk/step-free-tube-guide-map.pdf [Accessed 30 Apr. 2025].

3 responses to “IP Blogs”

-

Thanks for this insightful post – your lived experience managing the space really highlights how access is more than just a ramp or lift. I was especially struck by how transport and housing costs create hidden barriers, even when the building itself is accessible. It’s also frustrating how the flexible learning gains during the pandemic are now being rolled back. Your post makes me think: how can we reimagine these physical spaces to centre inclusion from the start, rather than as an add-on?

-

You highlight some really important points Ana- particularly the barriers that some students face before they’ve even arrived in the learning space, which will inevitably leave even the most dedicated students with less time and energy for their studies. Commuting seems to be a particularly big challenge for London-based students, and as it goes beyond the remit of a ‘campus’ falls beyond the ability of the university to change.

Perhaps further research could be done to create resources that would help students make informed decisions about accommodation before they arrive in London, based on the lived-experience of other students with disabilities, who can advise about the accessibility of transport and amenities.

-

Thanks Ana, this is great; very concise and to the point; and very much grounded in socio-economic conditions, which is a valuable framework for social justice approaches to EDI. Absolutely, a strong approach to take. When applying this to education, we can see that study after study shows that early years; parental/family income and location are the biggest factors of eventual educational success. And disability of course, without a focus on finance where would we be? Disability campaigners knew that had to take this approach to develop services. You analyse your own working space, which is a wonderful thing to do, thank you. It could be improved through personal reflection, student examples etc., but all in all a good job well done. You taught me something. As you often do! Much appreciated.

Leave a Reply to Elisenda Torras Cancel reply